Reinforced concrete is one of the most widely used construction materials in the world today. It combines the high compressive strength of concrete with the high tensile strength of steel, resulting in a composite material that is both strong and durable. This blog post explores what reinforced concrete is, how it works, its components, advantages, applications, and the science behind its incredible strength and versatility.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Reinforced Concrete

- Composition and Materials

- How Reinforced Concrete Works

- Types of Reinforcement

- Design Principles of Reinforced Concrete

- Advantages of Reinforced Concrete

- Applications of Reinforced Concrete

- Common Uses in Construction

- Durability and Maintenance

- Challenges and Limitations

- Innovations in Reinforced Concrete

- Conclusion

1. Introduction to Reinforced Concrete

Concrete has been used as a building material for thousands of years, dating back to ancient Roman architecture. However, plain concrete is strong under compression but weak under tension, which limits its use for structural elements subjected to bending or tensile forces. To overcome this limitation, engineers started embedding steel bars (rebar) inside the concrete, which gave birth to reinforced concrete.

Reinforced concrete is a composite material where steel reinforcement is embedded within concrete to carry tensile loads. This combination utilizes the best properties of both materials—concrete’s compressive strength and steel’s tensile strength—resulting in a material that can withstand various stresses and loads.

2. Composition and Materials

Concrete

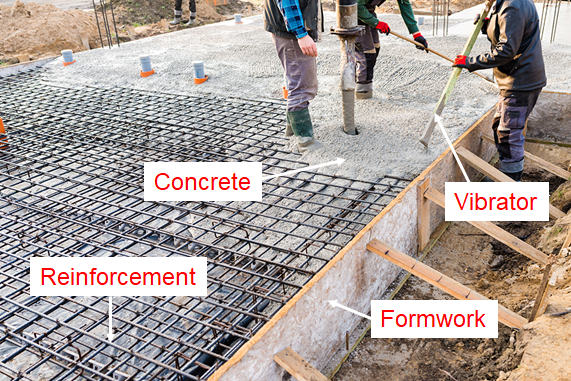

Concrete is a mixture of cement, water, aggregates (sand, gravel, or crushed stone), and sometimes admixtures to enhance properties such as workability or curing time. When water is added to cement, a chemical reaction called hydration occurs, which causes the mixture to harden and gain strength.

Steel Reinforcement

Steel used in reinforced concrete typically comes in the form of bars or mesh. These steel bars, commonly referred to as rebar, are designed with ridges or deformations to improve bonding with the concrete.

Steel is chosen because it has:

- High tensile strength

- Similar coefficient of thermal expansion as concrete (which minimizes stress from temperature changes)

- Good ductility, allowing it to deform before failure, providing warning signs before collapse.

3. How Reinforced Concrete Works

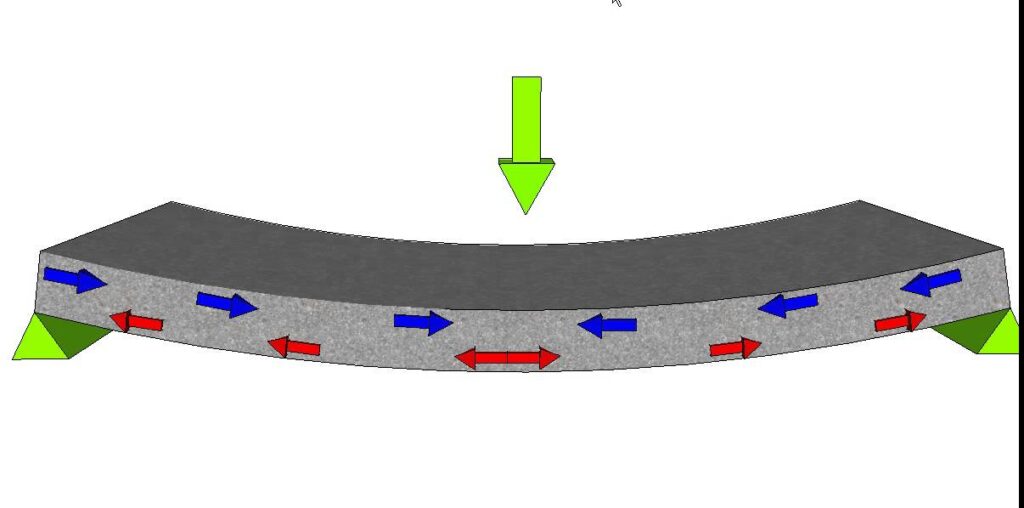

The fundamental principle behind reinforced concrete is the complementary behavior of concrete and steel under load.

- Concrete is strong in compression but weak in tension. It can bear heavy loads pushing or squeezing it but cracks under pulling or bending forces.

- Steel reinforcement is strong in tension. It can resist pulling or bending forces effectively.

When a reinforced concrete beam or slab is subjected to loads, the concrete handles the compressive forces, while the steel reinforcement takes the tensile forces. This synergy prevents cracking and failure, allowing for longer spans, larger loads, and more versatile structural designs.

Load Transfer Mechanism

When loads are applied to a reinforced concrete member:

- The concrete compresses, absorbing the compressive stresses.

- The steel bars carry the tensile stresses.

- The bond between steel and concrete ensures that the two materials act together without slipping.

This bond is critical. If the steel slips within the concrete, the structure loses integrity. The ribbed surface of rebar helps maintain this bond.

4. Types of Reinforcement

Reinforcement can come in several forms:

4.1 Steel Bars (Rebar)

The most common form. Available in various diameters and grades, rebar is laid out in specific patterns and quantities according to design requirements.

4.2 Steel Mesh or Welded Wire Fabric

Used commonly in slabs and walls, welded wire fabric consists of a grid of steel wires welded together at intersections.

4.3 Fiber Reinforcement

Fibers such as steel, glass, synthetic, or natural fibers are added directly to the concrete mix to improve tensile strength and control cracking.

4.4 Prestressed Reinforcement

In prestressed concrete, steel tendons or wires are tensioned before the concrete is poured, putting the concrete into compression. This technique allows for greater spans and thinner sections.

5. Design Principles of Reinforced Concrete

Designing reinforced concrete structures requires careful consideration of loads, stresses, materials, and safety factors.

5.1 Load Considerations

Designers consider dead loads (weight of the structure itself), live loads (occupants, furniture), environmental loads (wind, earthquake), and dynamic loads.

5.2 Stress Distribution

Engineers calculate bending moments, shear forces, and axial loads to determine the required amount and placement of reinforcement.

5.3 Safety Factors and Codes

Building codes provide guidelines for minimum reinforcement, concrete strength, and design safety factors to ensure structural reliability.

5.4 Detailing of Reinforcement

Proper placement, spacing, anchorage length, and cover (the distance between steel and the outer concrete surface) are crucial to protect steel from corrosion and ensure bonding.

6. Advantages of Reinforced Concrete

- High strength: Combines compressive strength of concrete and tensile strength of steel.

- Durability: Resistant to weather, fire, and corrosion (with proper cover and maintenance).

- Versatility: Can be cast into any shape, allowing architectural flexibility.

- Cost-effective: Materials are widely available and economical.

- Low maintenance: Requires minimal upkeep over its lifespan.

- Fire resistance: Concrete acts as a fire barrier protecting internal steel.

- Good thermal mass: Helps regulate building temperature.

7. Applications of Reinforced Concrete

Reinforced concrete is used extensively across many sectors:

- Residential buildings

- Commercial skyscrapers

- Bridges and flyovers

- Dams and water tanks

- Tunnels and underground structures

- Foundations and retaining walls

- Roads and pavements

- Industrial structures

8. Common Uses in Construction

8.1 Beams and Columns

Beams carry bending loads, with steel reinforcement placed mostly in the tension zones. Columns carry axial loads and may be reinforced in both directions.

8.2 Slabs and Floors

Reinforced concrete slabs are used for floors and roofs, often supported by beams or columns.

8.3 Foundations

Reinforced concrete footings distribute building loads to soil.

8.4 Retaining Walls

Hold back soil or water pressure.

8.5 Precast Elements

Walls, stairs, pipes, and modular units are often precast in factories and transported to site.

9. Durability and Maintenance

While reinforced concrete is durable, it is not immune to deterioration. Common issues include:

- Corrosion of steel: If water or chlorides penetrate the concrete cover, steel can rust, expand, and cause cracking.

- Freeze-thaw cycles: In cold climates, water in concrete pores can freeze and cause damage.

- Chemical attack: Sulfates and acids can degrade concrete.

Maintenance Practices

- Ensuring adequate concrete cover

- Using corrosion inhibitors or epoxy-coated rebar

- Regular inspections and repairs

- Proper drainage to prevent water accumulation

10. Challenges and Limitations

- Weight: Reinforced concrete structures tend to be heavier than steel structures.

- Cracking: Though controlled with reinforcement, cracks can occur due to temperature changes, shrinkage, or overloading.

- Construction time: Requires curing time before achieving full strength.

- Environmental impact: Cement production is energy-intensive and emits CO2.

11. Innovations in Reinforced Concrete

Modern research and technology have led to innovations improving reinforced concrete:

- High-Performance Concrete (HPC): Enhanced strength and durability.

- Fiber-Reinforced Concrete: Improves toughness and crack resistance.

- Self-Healing Concrete: Uses bacteria or chemical agents to repair cracks automatically.

- Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC): Extremely high strength and durability.

- Green Concrete: Incorporates recycled materials and reduces carbon footprint.

12. Conclusion

Reinforced concrete revolutionized construction by combining the best qualities of concrete and steel. Its ability to resist both compressive and tensile stresses makes it an indispensable material for modern infrastructure. Understanding how it works, its design principles, and maintenance needs is essential for engineers, architects, and construction professionals.

With ongoing innovations, reinforced concrete continues to evolve, promising even greater strength, sustainability, and versatility for the future of construction.

References:

- Neville, A. M. (2011). Properties of Concrete. Pearson Education.

- Mindess, S., Young, J. F., & Darwin, D. (2003). Concrete. Prentice Hall.

- ACI Committee 318. (2019). Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete. American Concrete Institute.

- Mehta, P. K., & Monteiro, P. J. M. (2014). Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials. McGraw-Hill Education.

Thank you for reading! If you found this article helpful, please share it with others interested in construction and civil engineering. For more such content, subscribe to our newsletter.